US Labor Market: The Resilient "Streak"er

I want to highlight and celebrate the most important “streak”er to the United States economy: the US labor market.

In the spirit of John Cena at this year’s Oscars—whose streaker bit was a reference to a different Oscars streaker from 50 years ago1—I want to highlight and celebrate the most important “streak”er to the United States economy: the US labor market. Although the job market has shown some recent weakness,2 its current streak of now 40 consecutive months of positive job growth is representative of a broader trend.

Despite having a few other 20-year periods of labor market performance similar to the last 20 years in terms of total job growth and average job growth, there is one dimension on which the last 2 decades are unmatched. No previous 20-year period has had more streaks of consecutive positive employment months, nor has any previous period’s streaks had more total jobs added than those of our most recent two decades.3

Figure 1 plots each of the 83 positive consecutive US nonfarm employment streaks since January 1939, also showing the cumulative employment total over each streak. The orange streaks are the shortest and smallest streaks in terms of both consecutive months (< 40) and cumulative employment gains (< 10 million), respectively, and are not labeled in the legend. The remaining 7 streaks have either consecutive positive employment months greater than or equal to 40 (longest) or cumulative employment gains of more than 10 million (largest) and are labeled in the legend, with the most recent streaks being dark purple and the older streaks fading to green then yellow.

Figure 1. US employment streaks: consecutive positive monthly gains and cumulative employment gains, 1939 to 2024

Table 1 shows the statistics for those 7 longest or biggest streaks. Obviously, positive employment streaks that last the longest will tend to have the largest total employment gain, as is the case with the 2010-2020 streak. For this reason, I also calculate the average monthly employment gain for each streak.

I have highlighted in yellow the rows in Table1 for the four most recent large streaks, starting in 2003, 2010, 2020, and 2021, respectively. It is interesting to note that the 7-month COVID recovery streak from May to November 2020 added nearly the same number of total jobs (12.3 million) as the positive streak of nearly 4 years from July 1975 to March 1979 (13.0 million jobs).

Figure 2 shows a scatterplot for all the 83 consecutive positive employment streaks in the US data with months in streak on the x-axis and average monthly employment gain across the streak on the y-axis. Not only is our current streak of 40 consecutive positive months (January 2021 to present April 2024) ranked 5th highest among the 83 total consecutive streaks, but it is also ranked 5th highest in terms of average monthly employment gain during the streak.

Figure 2. US employment streaks: consecutive positive monthly gains and average monthly employment gains, 1939 to 2024

Resilient employment in the face of headwinds

The broad US labor market has been the steady foundation to which our recent economic resilience has been anchored.

Last week’s US GDP report came in lower than expected at 1.6% annual growth, inflation has been significantly higher than its 2% target level since March 2021, and the most recent nonfarm job openings data released two days ago was at a 3-year low. But the US labor market has been surprisingly resilient in the face of these headwinds. Figure 3 shows the time series of monthly US nonfarm employment from July 1919 to the most recent month.4 The vertical gray bars designate periods of recession.

Figure 3. US nonfarm employment, monthly, seasonally adjusted: 1919 to 2024

When you look at the Figure 3, the most prominent characteristics are the three biggest drops in employment at the beginning of the Great Depression (Aug. 1929 to Mar. 1933), the Great Recession (Dec. 2007 to Jun. 2009), and the COVID-19 pandemic recession (Feb. to Apr. 2020), and the otherwise steady upward trend of growth in US jobs.

The average time between recessions since 1945 has been 5 years and 5 months.5 The time since the end of our last recession has been 4 years. The US will certainly experience another recession in coming years. And there is always a chance that an economic slowdown arrives sooner than later. But I want to highlight and celebrate the broad US labor market, which has been the steady foundation to which our recent economic resilience has been anchored.

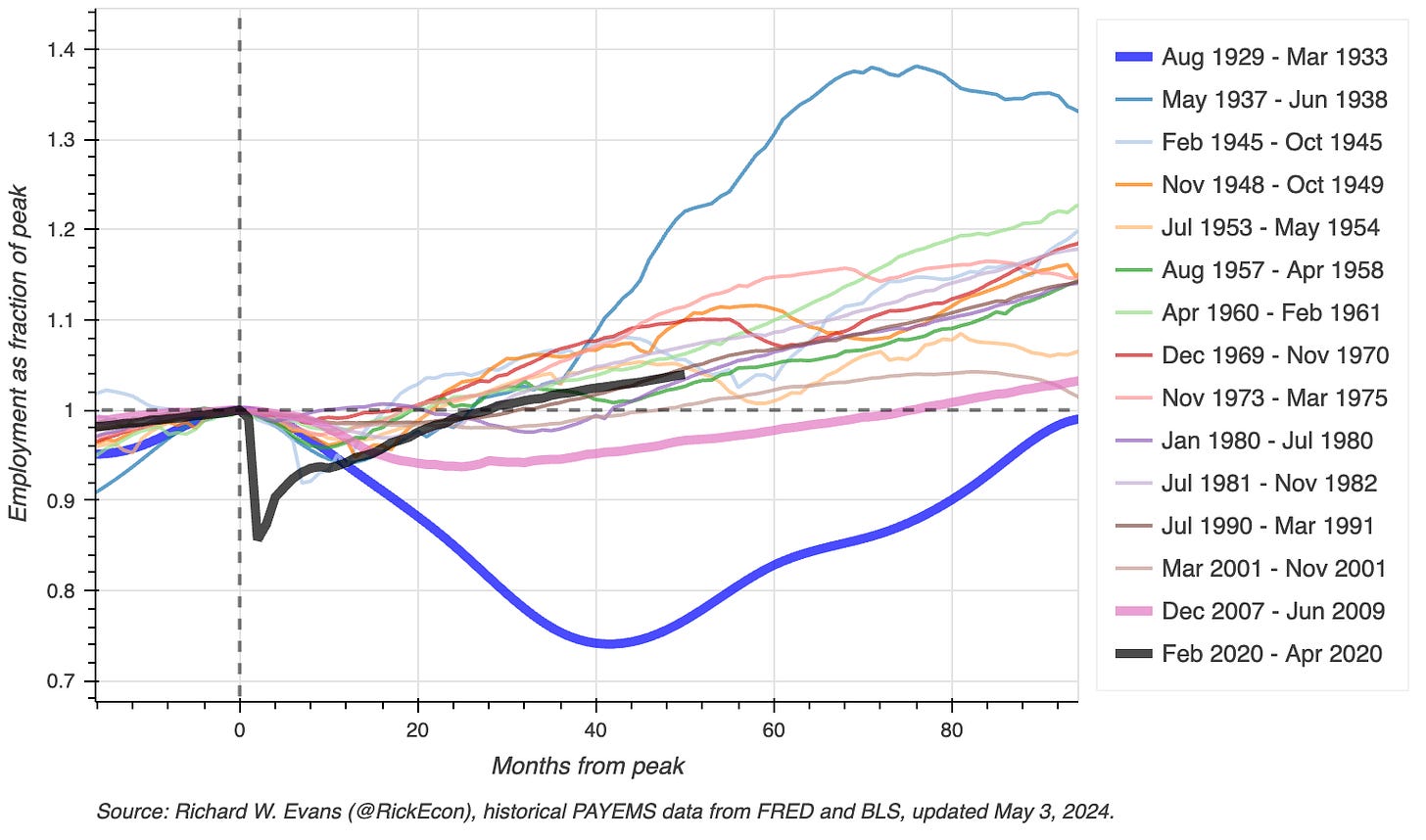

Figure 4 gives a cleaner comparison of employment losses and subsequent recoveries at the beginning of each of the last 15 recessions, from the Great Depression to the most recent COVID-19 pandemic recession. Figure 4 is a normalized peak plot in which the peak employment level at the beginning of each recession is normalized to a value of 1.0, then each previous value and each subsequent employment level is shown as a percentage of that peak value.

Figure 4. US nonfarm employment, normalized peak plot, comparison of last 15 recessions, 1929 to 2024

Figure 4 shows how historically unprecedented were the employment losses at the outset of the most recent COVID recession (bold black line). But we also start to see that the employment recovery since the COVID recession has been extraordinarily steady. The steady upward climb of the most recent positive employment streak (Jan. 2021 to Apr. 2024) has been historically strong, as we observed in Figures 1 and 2 and in Table 1.

And the longest positive employment streak of 113 months from Oct. 2010 to Feb. 2020 (nearly 10 years) came on the heals of the Great Recession of 2007-2008, one the biggest economic shocks since the Great Depression. It is interesting to note from Figure 4 that the labor market after the Great Recession (bold pink line for recession Dec. 2007 to Jun. 2009) took 76 months (more than 6 years) to get back to its pre-recession levels.

I close this article with one final table of what the US labor market has done in the last 20 years (and 7 months) since the beginning of the September 2003 consecutive positive employment streak. The US economy has added 28.0 million jobs since September 2003, an increase of 21.5 percent. Table 2 decomposes those job gains into the job gains in the most important broad US industry categories.

The total employment in the industries in Table 2 add up to total US nonfarm employment. While it is true that the broad services industries have grown the most, it is not true that blue-collar jobs have declined the most. Among blue-collar industries, manufacturing has lost the most jobs with a 9.7% decline over the last two decades. But other blue-collar industries, such as Mining and Logging and Construction increased by 12.5% and 21.2%, respectively.

The biggest winner over the last 20 years was Transportation and Warehousing, with an increase of 57.3%. Similar to Wholesale Trade (also up 11.4%), Transportation and Warehousing is largely an intermediate goods industry. It often involves trade between producers. The fact that this was the highest growth industry in the US over the last 20 years suggests that the main engine of growth in the US economy is more about the relentless march forward of our broad production sectors, and not just a shift from manufacturing to services industries.

Epilogue

This US labor market strength seems to come from deeper cultural and institutional advantages than any one political party or ideology can claim. The four major positive employment streaks from the last two decades cut squarely across four presidential administrations that included two Republican Presidents and two Democratic Presidents.

In some cases, recovering from big negative economic shocks has required long, steady, and reliable creation of new jobs. But in all cases, the performance of the US labor market demonstrates a dynamism and resilience that is the envy of the world.

A note on open source resources and replicating these data and images

All the source data and corresponding data visualizations from this article can be obtained and replicated by running the code locally on your personal computer by using the resources in the USempl_Streaks-2024-05 (https://github.com/OpenSourceEcon/USempl-Streaks-2024-05) GitHub repository. Instructions are found in the Jupyter notebook USemplStreaks.ipynb in the repository. One advantage of creating the images on your local machine is that the images created with the Python code have more dynamic functionality, including mouse hover-over full data description, muting and unmuting of particular series, zoom, and selection.

See Lenker, Maureen Lee, “Naked John Cena pays tribute to 50th anniversary of Oscars streaker,” Entertainment Weekly (Mar. 10, 2024).

In data released two days ago (May 1, 2024), US total nonfarm job openings were at their lowest level in three years (since March 2021). See this Federal Reserve Economic Data chart. Data come from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS), May 1, 2024 release.

It is also true that the last two decades have seen the two biggest negative shocks to the US economy since the Great Depression. During the Great Recession (Dec. 2007 to Jun. 2009), the US job market lost 8,695,000 jobs in the 25 months between January 2008 and February 2010 (-6.3%). And during the COVID-19 pandemic recession (Feb. to Apr. 2020), the US job market lost a record 21,888,000 jobs in the two months between February and April 2020 (-14.4%). As a comparison, the US job market lost 25.9% of its jobs in the first 41 months of the Great Depression between July 1929 and December 1932. Figure 4 shows that, in the first six months of any of the previous 15 recessions, the COVID-19 pandemic recession was more severe than any of the previous 15 recessions, including the Great Depression and the Great Recession, with a 7.6% decline in US jobs. It is also interesting to note that for the period from 16 months after the beginning of a recession to 91 months (7 years and 7 months), the Great Recession (Dec. 2007 to Jun. 2009) saw the second-most-negative impact on the labor market, surpassed only the by the Great Depression.

The monthly US nonfarm employment data only go back to January 1939. I created the red line from July 1919 to December 1938 by fitting a cubic spline interpolation to the annual US nonfarm employment data from that period.

I measure time between recessions as the time between the economic trough (end of a recession) to the next economic peak (beginning of the next recession) as measured by the National Bureau of Economic Research Business Cycle Dating Committee. See https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions.